So many connections passed through my mind last night as I watched the premiere of Bjork’s Cornucopia, an original production conceived for The Shed.

It was my first visit to The Shed and I was only able to peek into a couple of the other spaces, so I cannot really comment on them other than to say the space is huge and it has the misfortune to be adjacent to the Hudson Yards garish neon commercial signs and the hulking Heatherwick stairway to nowhere. The whole thing, the hall, the production, the staffing is certainly a massively expensive undertaking and one cannot help but think of all the theaters in NY in dire need of funding.

But once inside the McCourt theater I understood that The Shed was an excellent space for accommodating the visions of people who think BIG. (As an Angeleno I held myself in check from allowing any reflux from the disastrous McCourt stewardship of the Dodgers to affect my reactions. It’s not only arms manufacturer and oil company trustees who should be held to account.)

Architect Liz Diller, who slipped into the performance just after it had begun, and Bjork and her creative team think big and I admire that. We don’t have enough women thinking big in this very fearless way. The McCourt has every production bell and whistle imaginable, and they were used in full measure for Bjork’s grand vision of Utopia.

I confess I hadn’t been to a pop concert in a long time, and I imagine that digital visual is also being used by other performers. But there could be no more immersive production than this one. The Met Opera in New York and Artistic Director Alex Poot’s former digs at the Park Avenue Armory and Madison Square Garden are the only spaces I can think of in New York that could accommodate this kind of production grandeur.

Bjork has imagined a world where children have a true voice. The appearance at the outset of The Hamrahlio childrens choir in front of the stage set that tone immediately. In their Icelandic costumes they welcomed the sold out audience with runes and sopranos that warmed up the vast hall considerably. In fact Iceland is evoked in many ways throughout the performance.

Bjork’s back up performers on stage are a troupe of Midsummer Night’s Dream-ian fairy sprites (all with the Iceland surnames of ---dottir) who can play a mean flute, even if the instruments have been molded into a circle which surrounds Bjork for four to play at one time, and they dance, cavort and lead us into Bjork’s unique world.

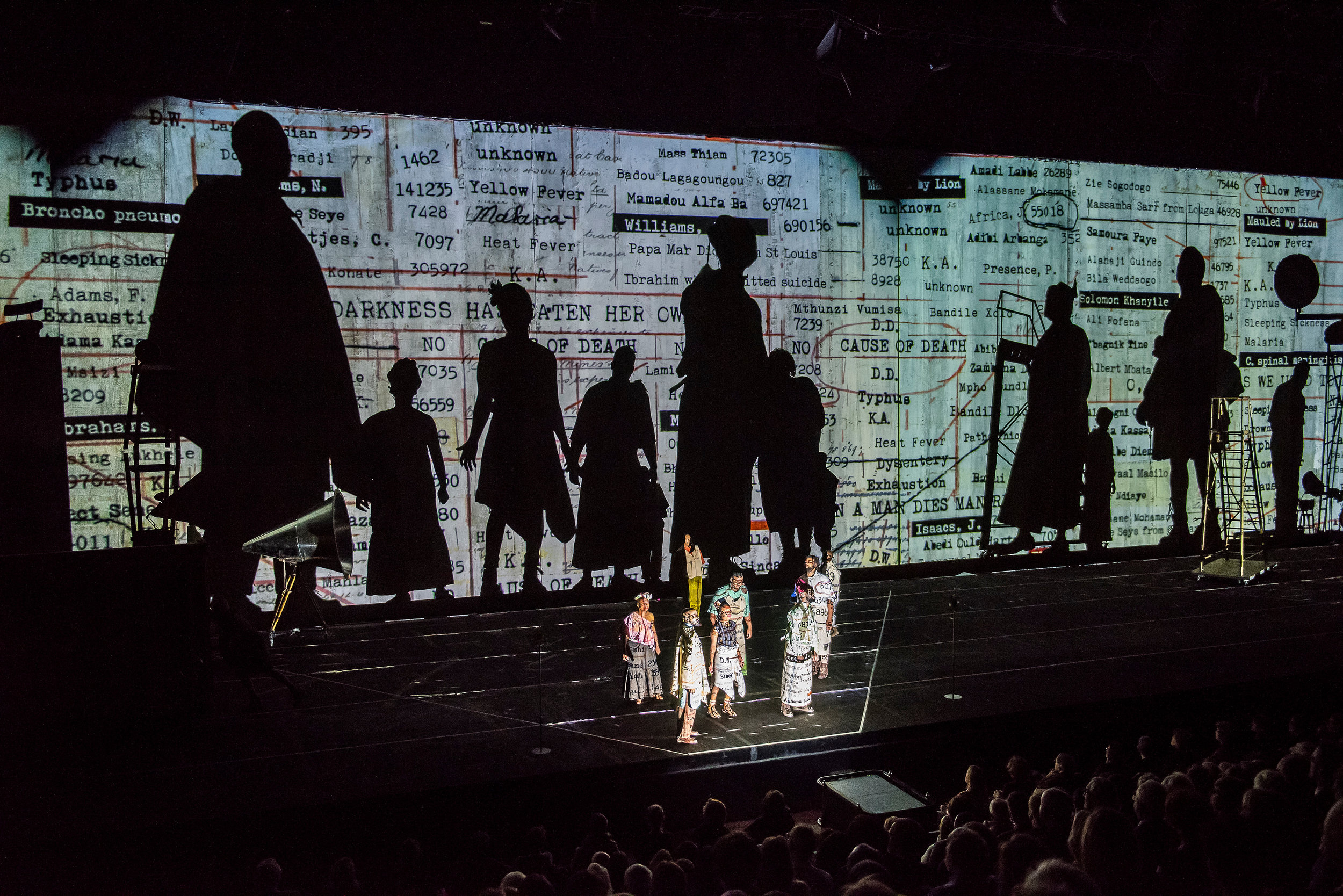

Bjork’s other collaborators--all overseen by director Lucrecia Martel--a production designer, Chiara Stephenson who did the magic mushroom-like platforms, a veteran drummer Manu Delago who roves to many stations and alt-percussive instruments (a watery tank a particular favorite of mine), a media artist Tobias Gremmier whose digital projections on a beaded curtain (Four Seasons restaurant anyone?) and a rear wall were a combination of Georgia O’Keefe and Karl Blossfeldt floral stamens and pistils, costume designers Iris Van Herpen who outfitted Bjork first in white puffed balls and a black ruff (very eighties, it reminded me of my wedding dress which was made with the BIG puffy sleeves then in style) and then Olivier Rousteing’s gossamer feathered birdlike contraption, and James Merry who did the many headpieces which were very Klingon-like and mostly obscured Bjork’s face, all combined in this fantasia which begins and ends with Bjork’s vision for our planet.

She’s worried. A dire message about global warming appears on the curtain. The young Swedish girl who began the global school walk-out movement is also given curtain time to make her case that adults are now behaving like selfish, spoiled children intent on wrecking our precious resources.

The production has an Alice in Wonderland-slipping-down-the-rabbit-hole feel but as someone who is not entirely familiar with the Bjork canon, I can only say that sometimes I wished for more Bjork and less production. When she steps out in front of the curtain onto a small platform and into the audience there is a certain raw, unadorned quality that is very meaningful.

Nevertheless, her heart is all over this outsize confection which runs the full month (I hear it is sold out) and her originality and dedication to her work is apparent in everything she sings and every move she makes. Under the Big Top of The Shed, she still manages to emerge as a truly original visionary. I look forward to catching up with the other project spaces soon.

Photos: Santiago Felipe, 2019. Courtesy One Little Indian/The Shed