Like Warhol, Dorothea Tanning, the subject of a new retrospective at the Tate, toiled first in advertising when she came to New York. She had been deeply affected by the groundbreaking MoMA Surrealism/Dada show of 1936 and her ads for Macy’s and others reflected this new awareness of the ability to disassociate body parts and imagery.

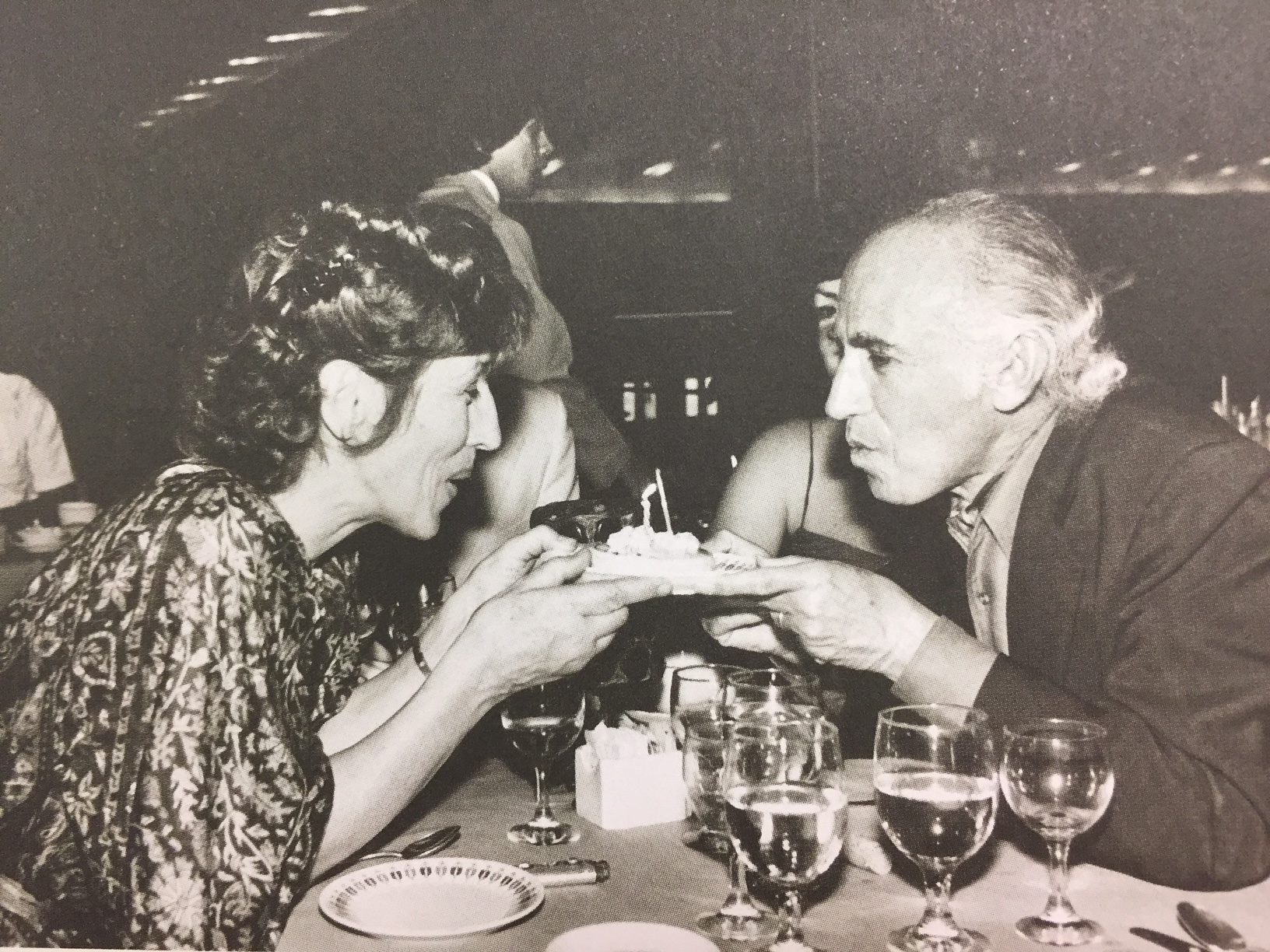

She herself was selected by her future husband Max Ernst—then married to Peggy Guggenheim—for a show of women artists at Guggenheim’s Art of this Century gallery when she returned from a stay in Europe. (Was this the moment of the Ernst-Tanning coup de foudre? A year later they were together) Georgia O’Keefe refused to be relegated to this show of ‘women artists” but Tanning accepted. When next invited to participate however in a women-only show in the 70’s second wave of feminism, like many creative women who had already made their own way (Mary McCarthy, Lillian Hellman et al) Tanning was also finally a refusnik. ‘Women artists,” she said, “There is no such thing – or person. It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as “man artist” or “elephant artist”. You may be a woman and you may be an artist; but the one is a given and the other is you.’

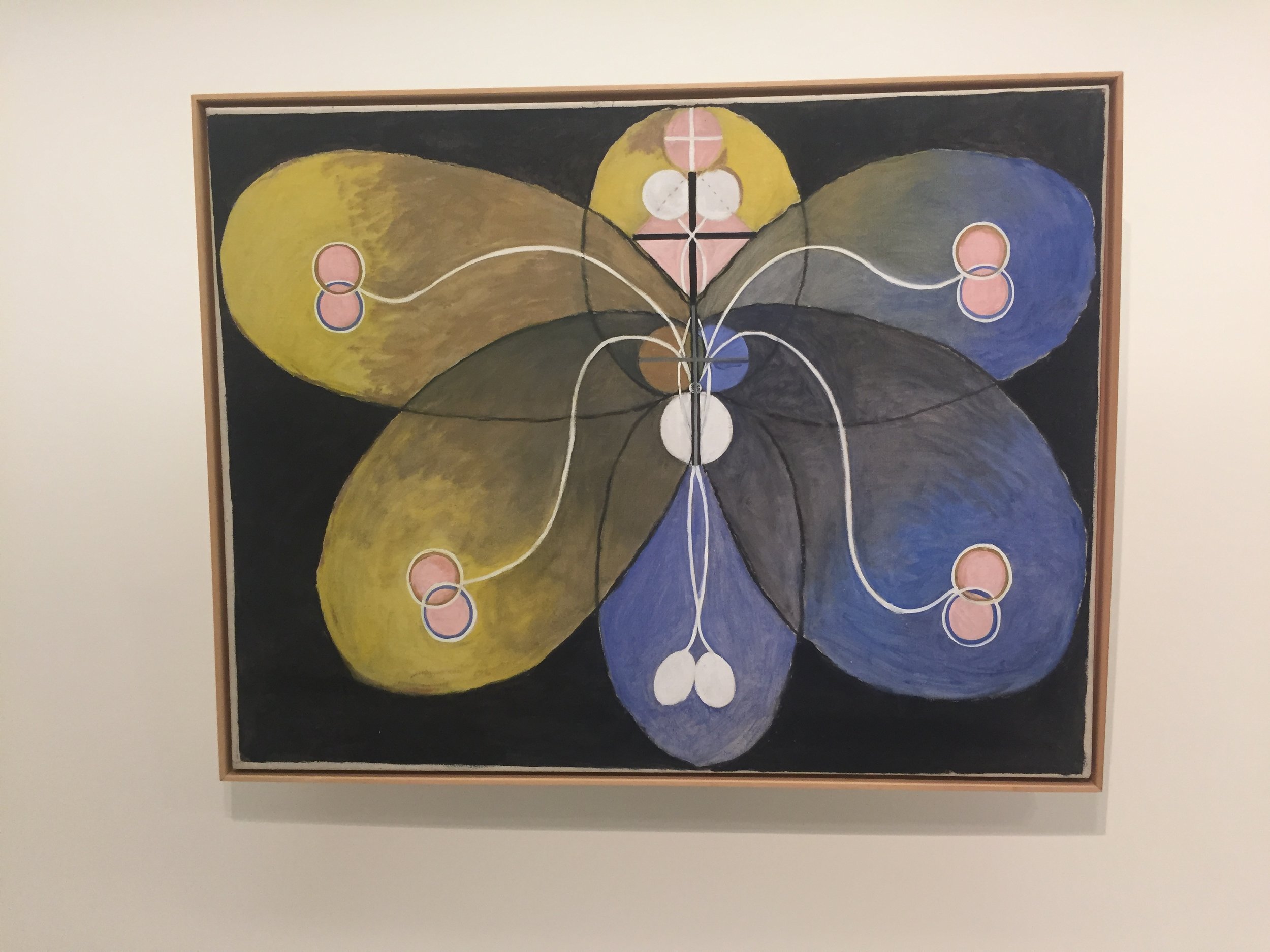

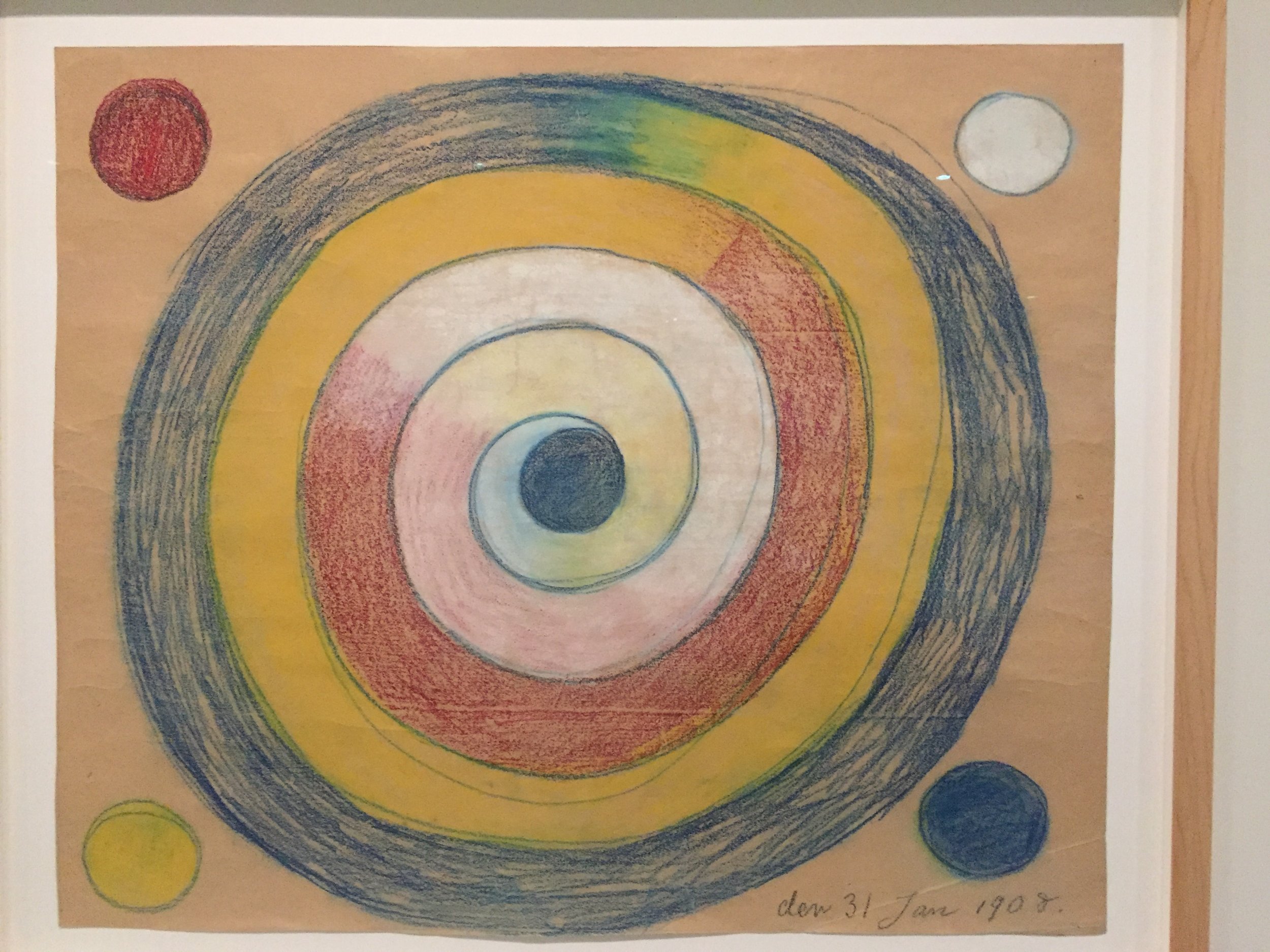

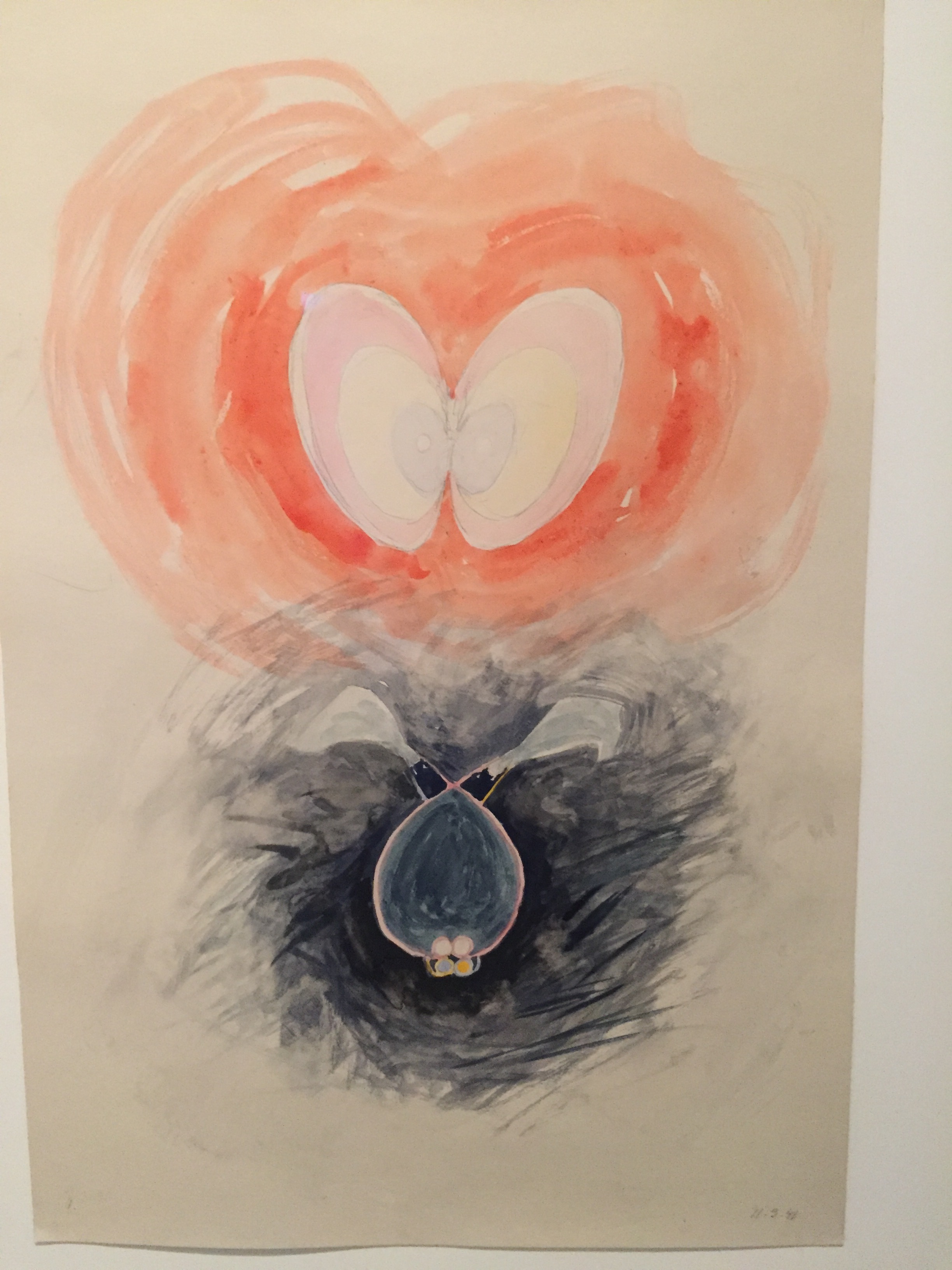

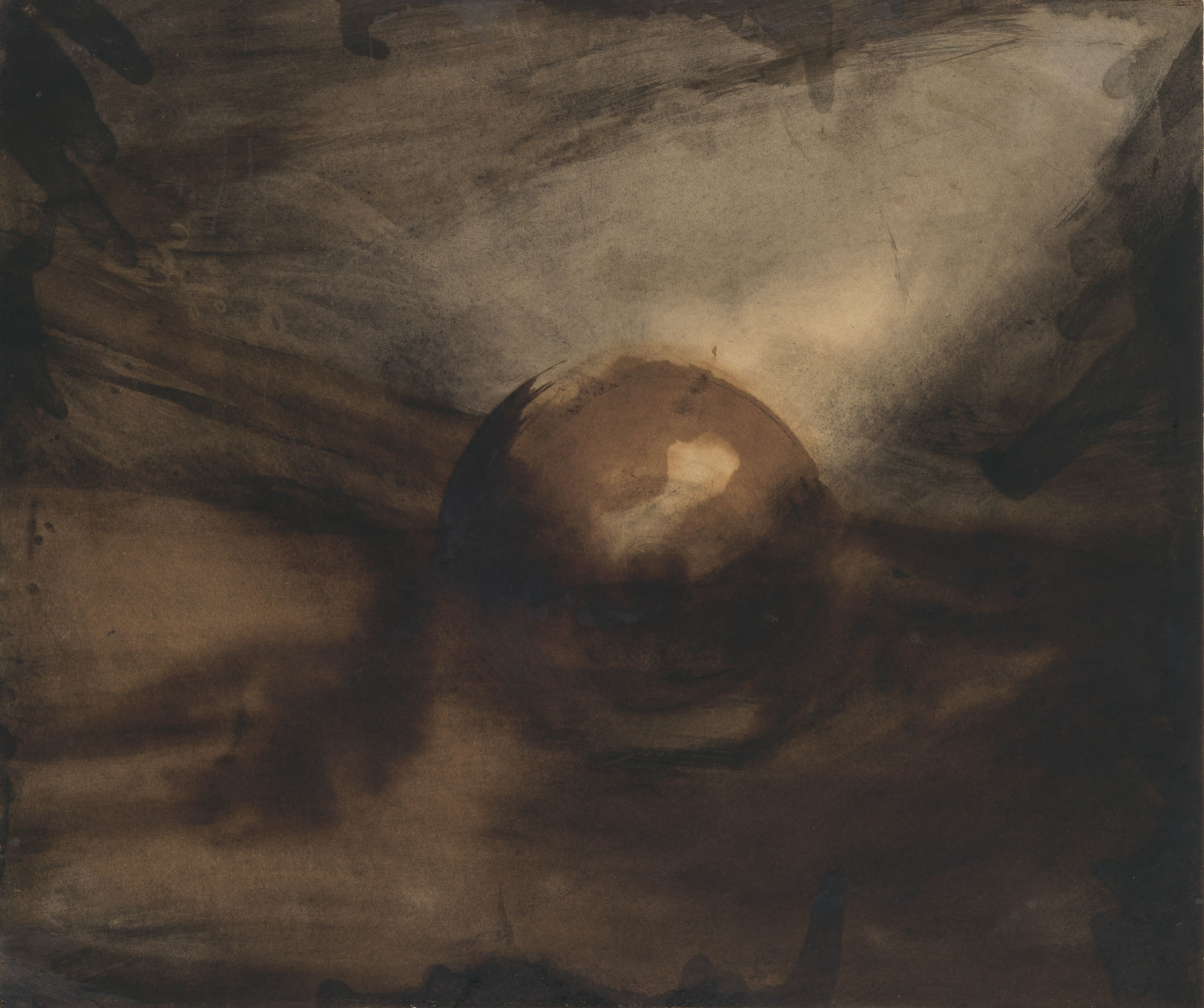

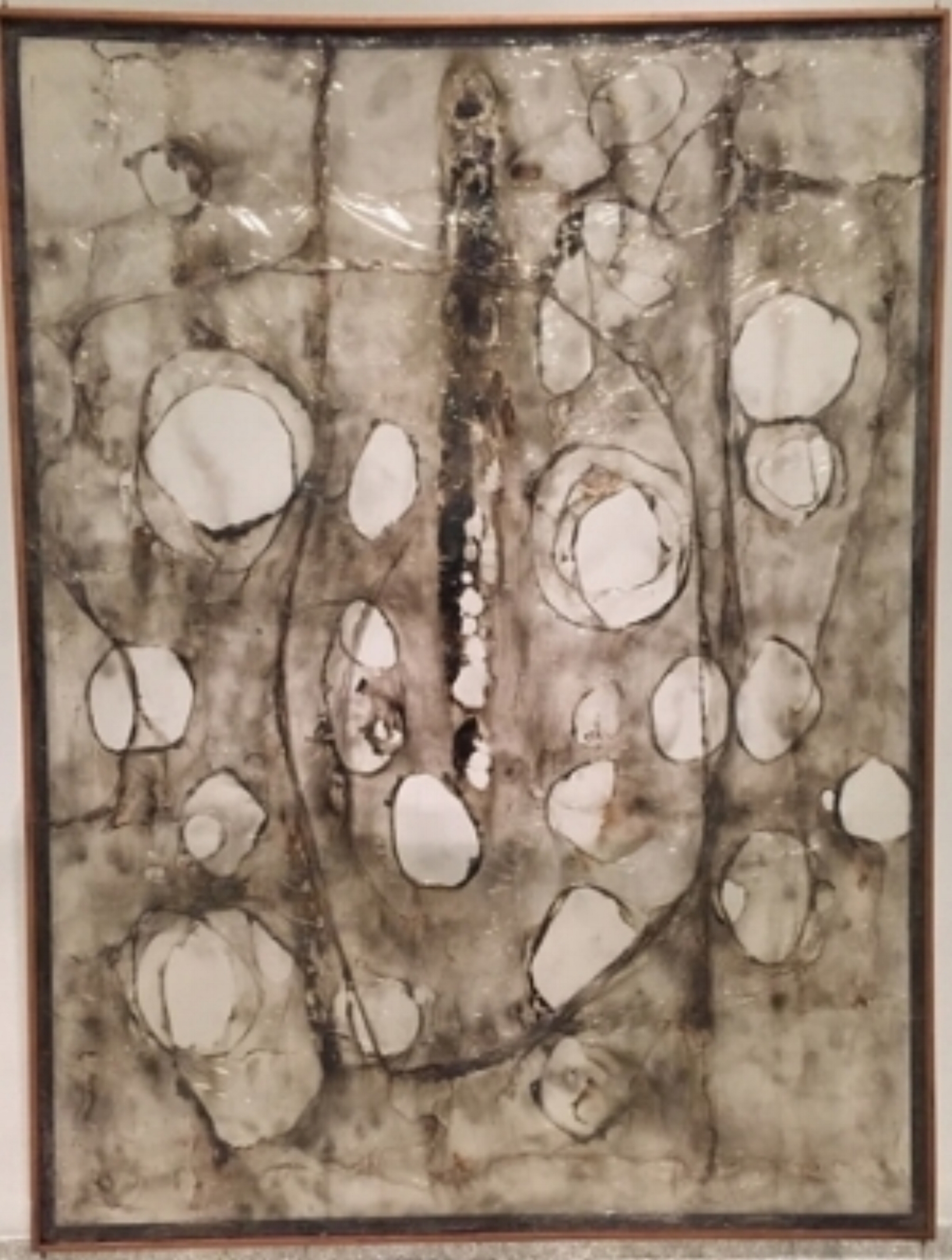

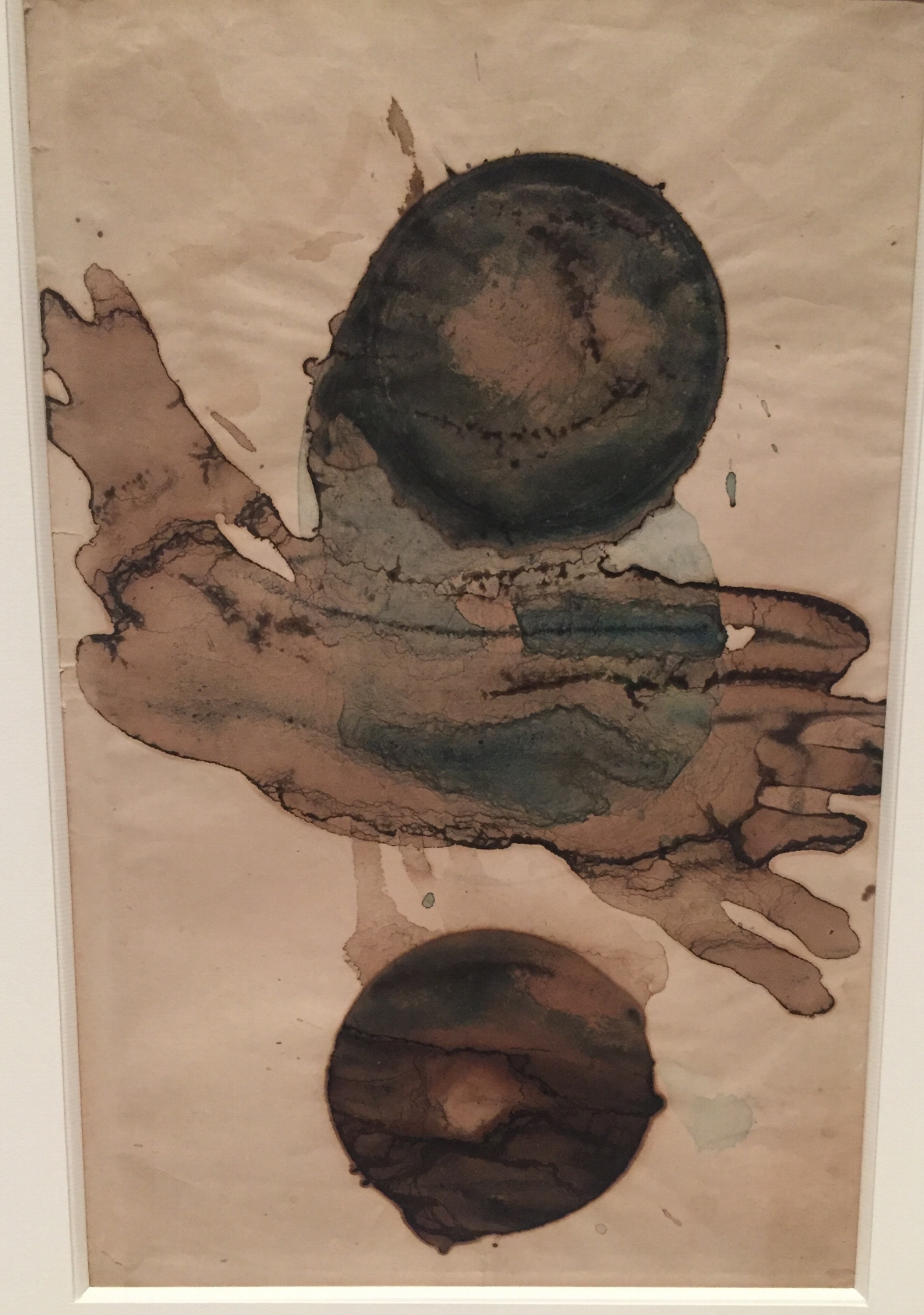

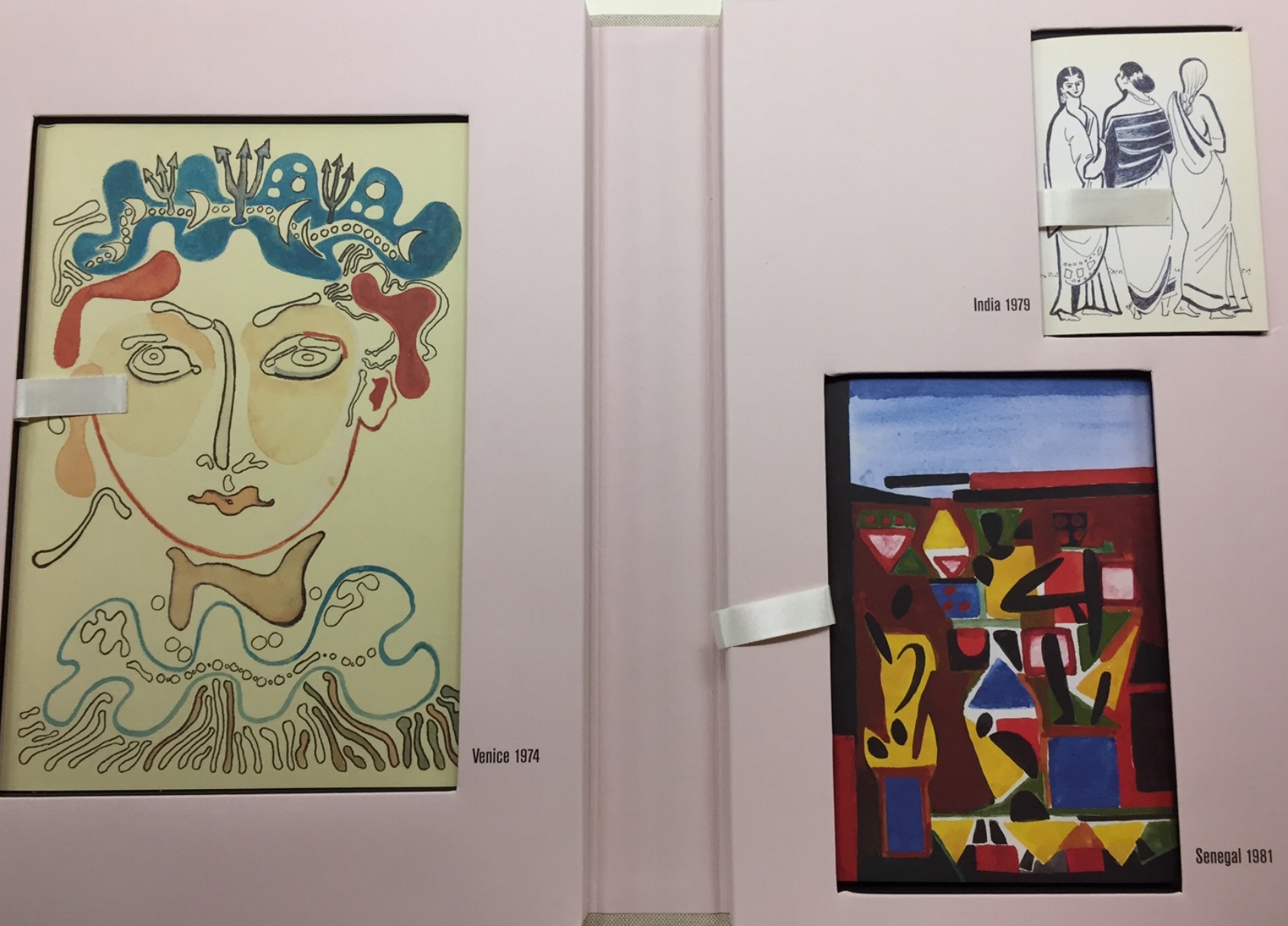

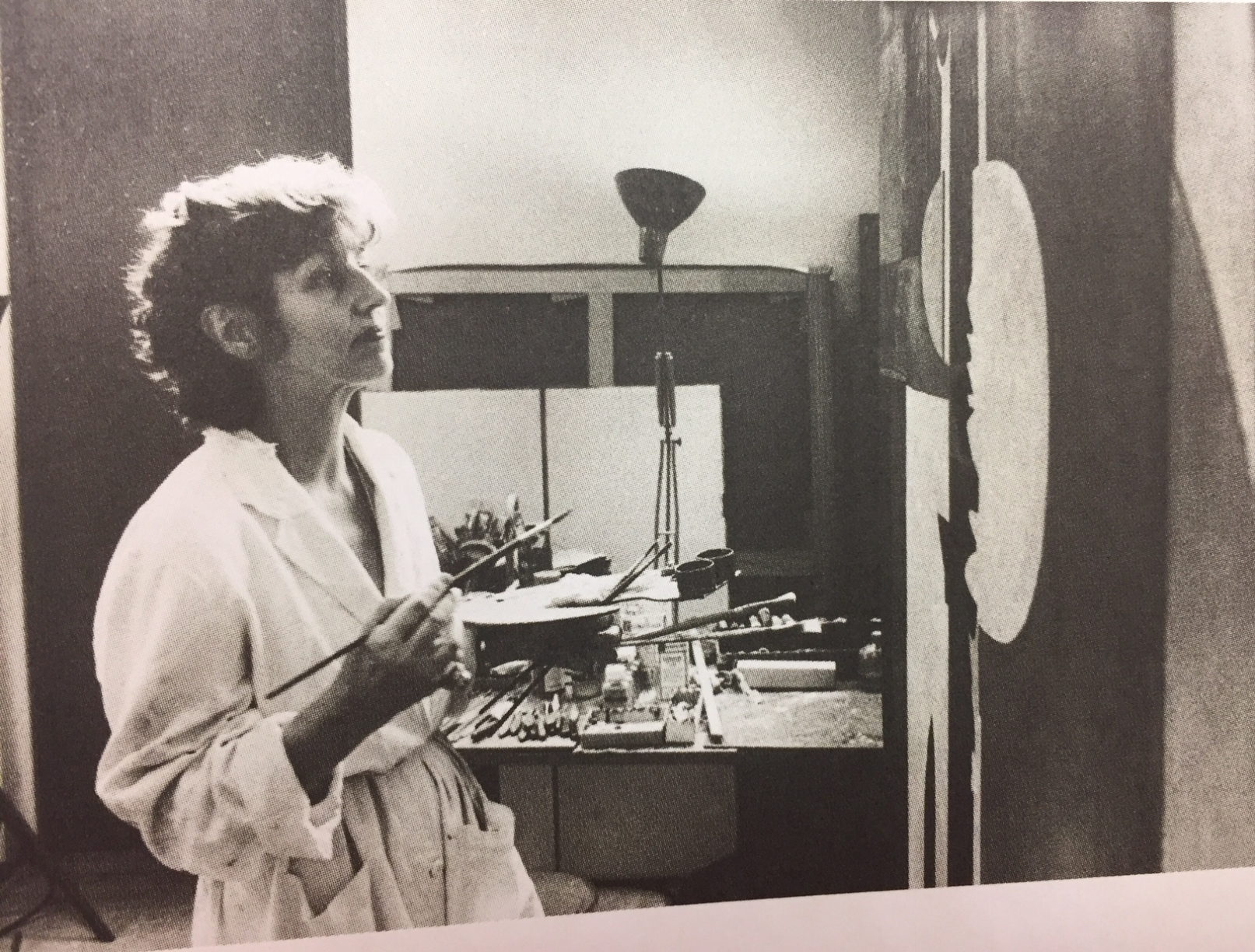

She had by then grown into a bold, incisive, self-confident practitioner of painting, poetry, sculpture, costumes and set design.

"Just put yourself in my place, George, " she wrote after she had, in a labor of love, produced the costumes and sets for Balanchine’s new ballet Night Shadow, supported by Lincoln Kirstein, "and you would cry too." Tanning was passionate about ballet, but her production had an unfortunately short shelf life when a new production by the Monte Carlo ballet appeared just a few years later. "I really thought all this time that I had helped to make it a good work, and lots of other people thought so too. I was proud to have worked with you to make such a pretty ballet and I felt it was a real collaboration of all 3 of us. But I suppose it’s a very complicated story and I don’t understand very well how these things work."

Tanning went on to work on other ballets and had plans for many more, but was thwarted by lack of funding and the nature of the collaborative process which stymied her as a solo practitioner .

I wonder what Tanning would have made of the many women-only international shows organized this year in response to #MeToo. Ghetto or Gift? The concurrent counter narrative solo exhibitions—besides Tanning (Ernst), Lee Miller(Man Ray) and Gala Eluard (Dali)—who have finally been removed from the rolls of the ‘muses’-only, tell a more complete tale.

The exhibition runs from February 27 to June 9, 2019 at the Tate Modern. All images courtesy of the Tate.