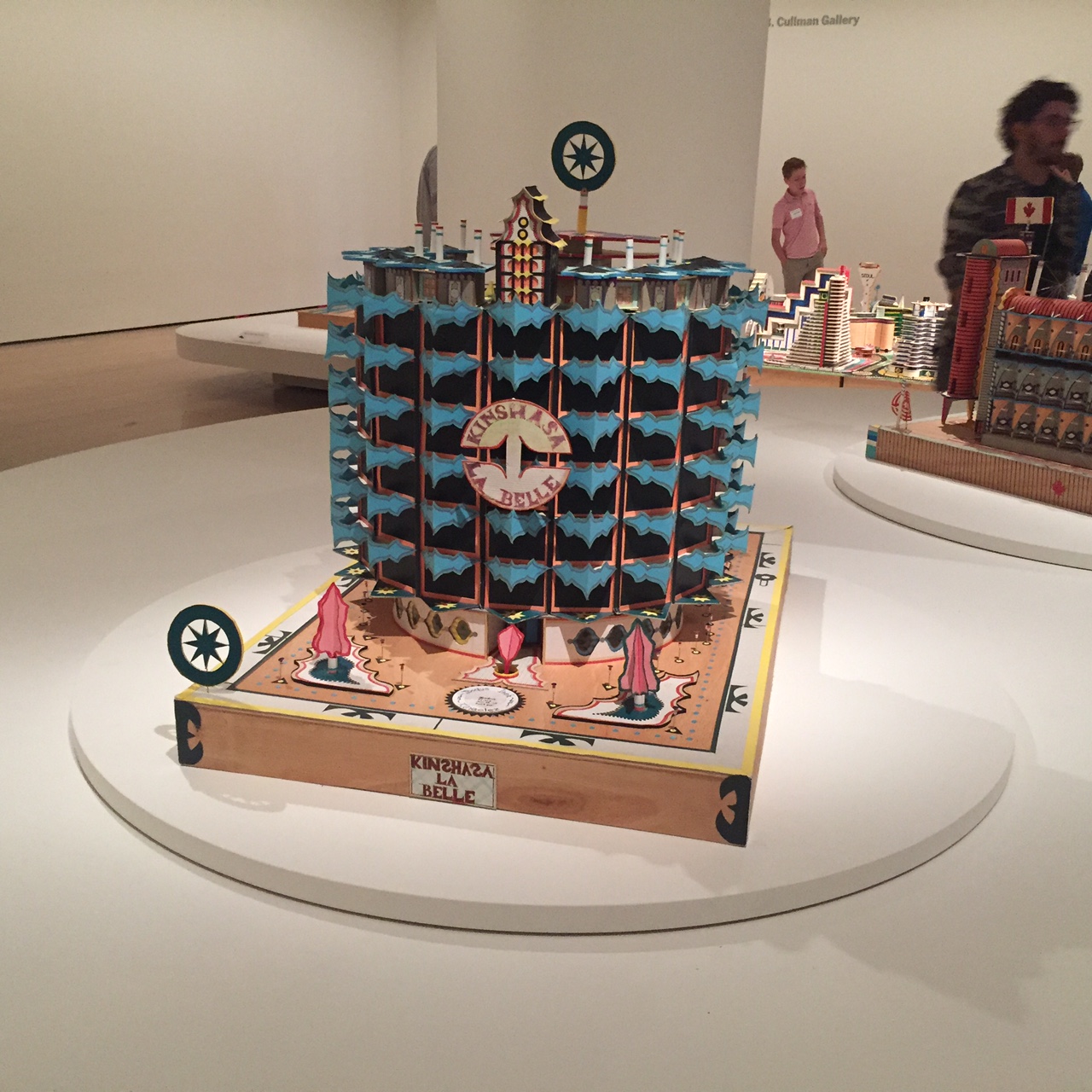

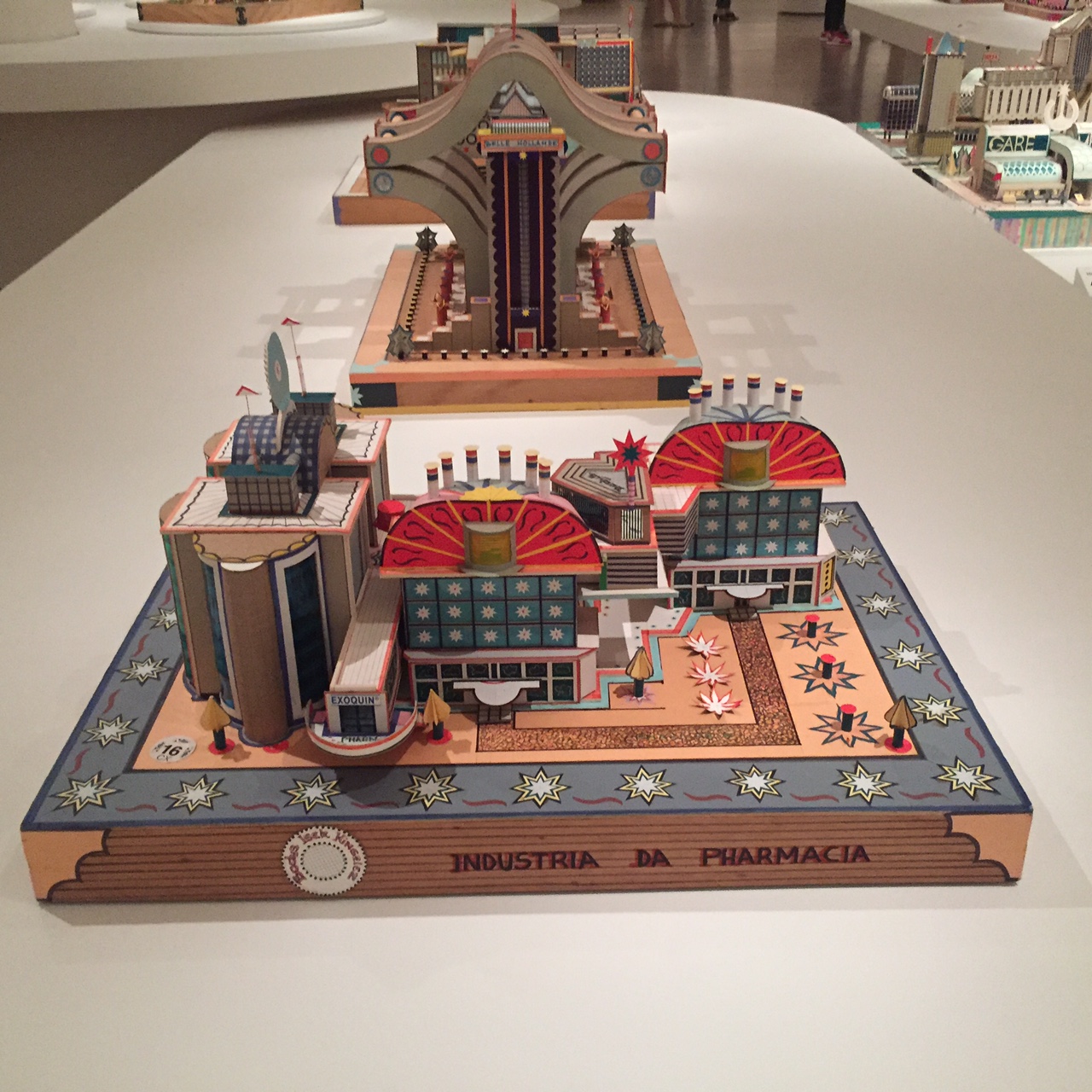

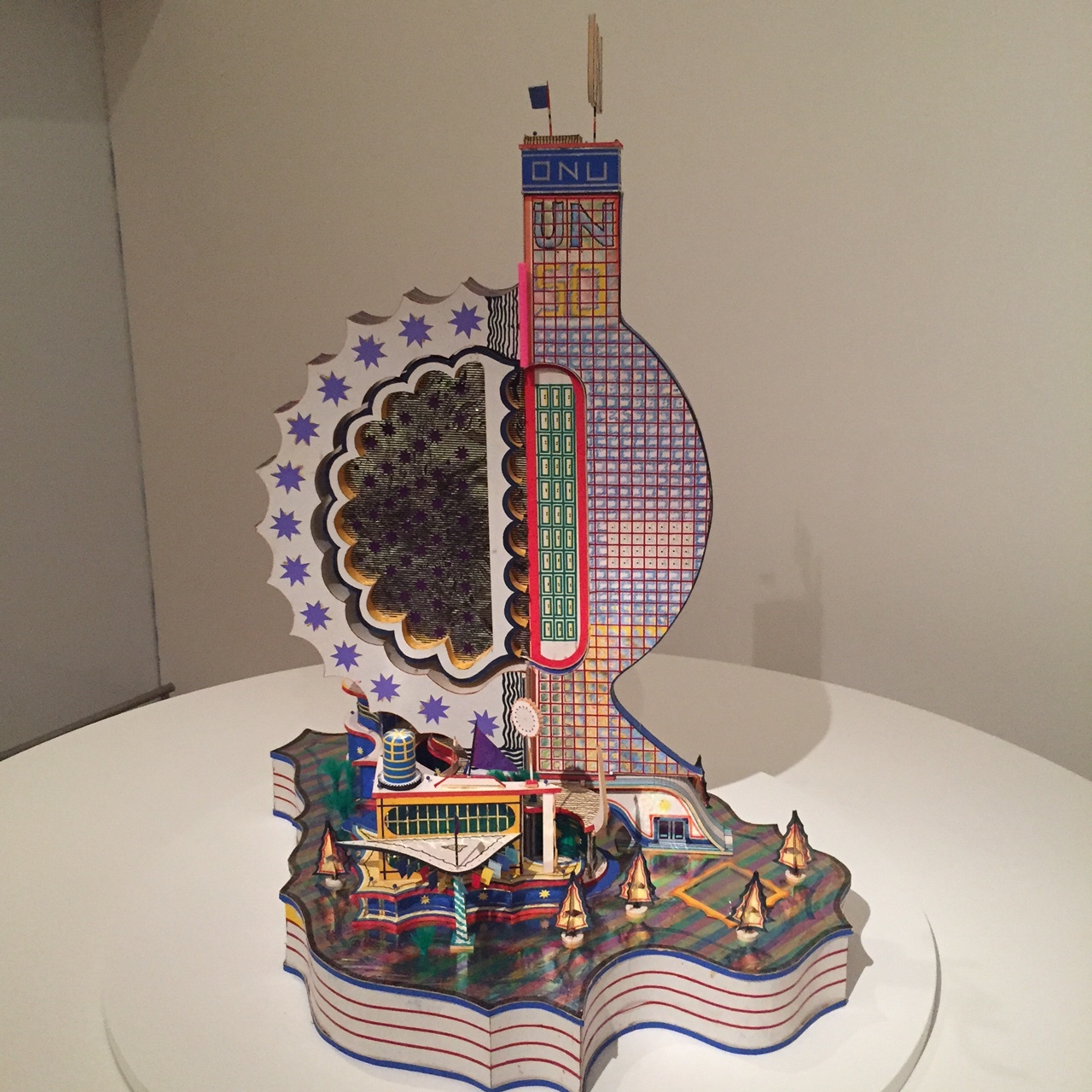

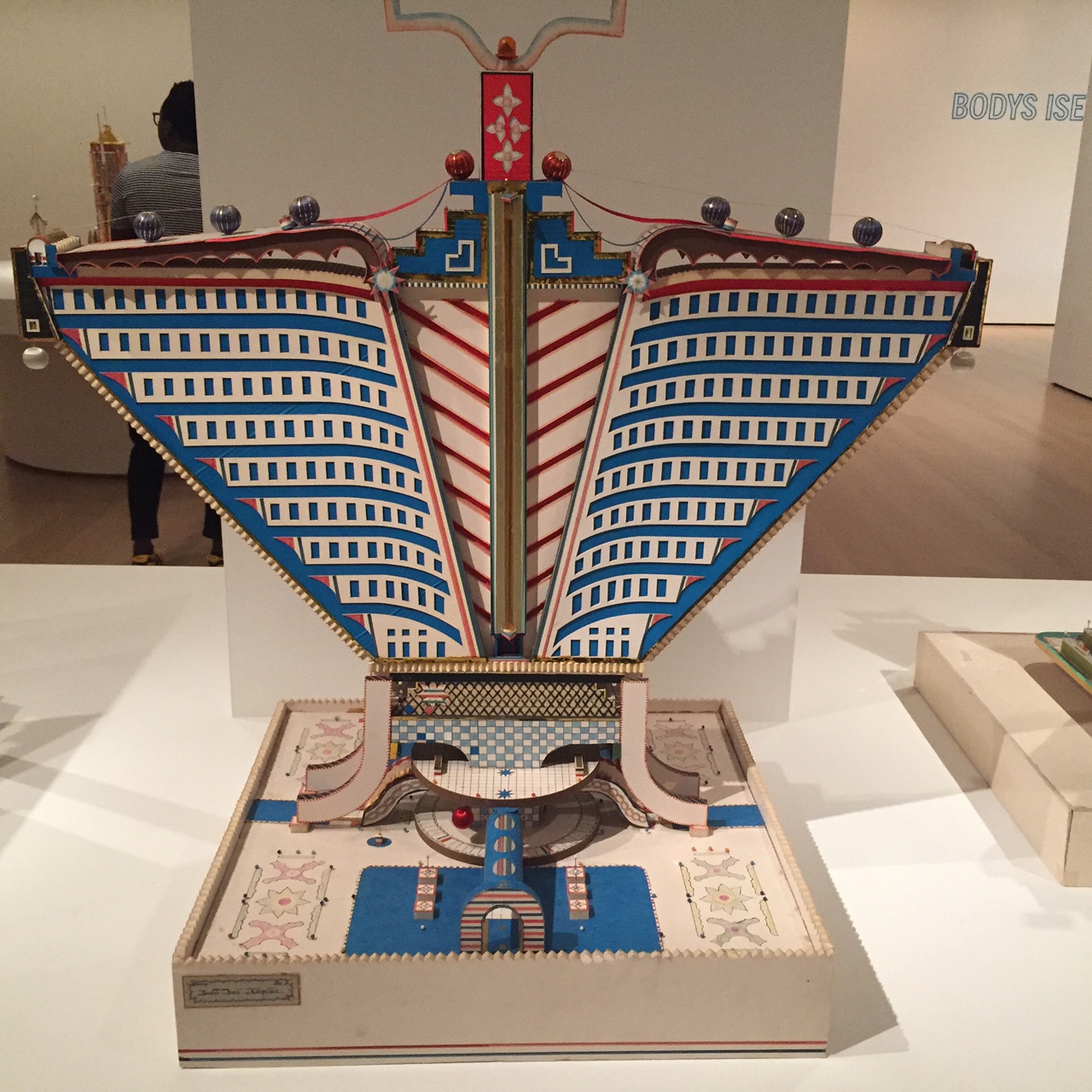

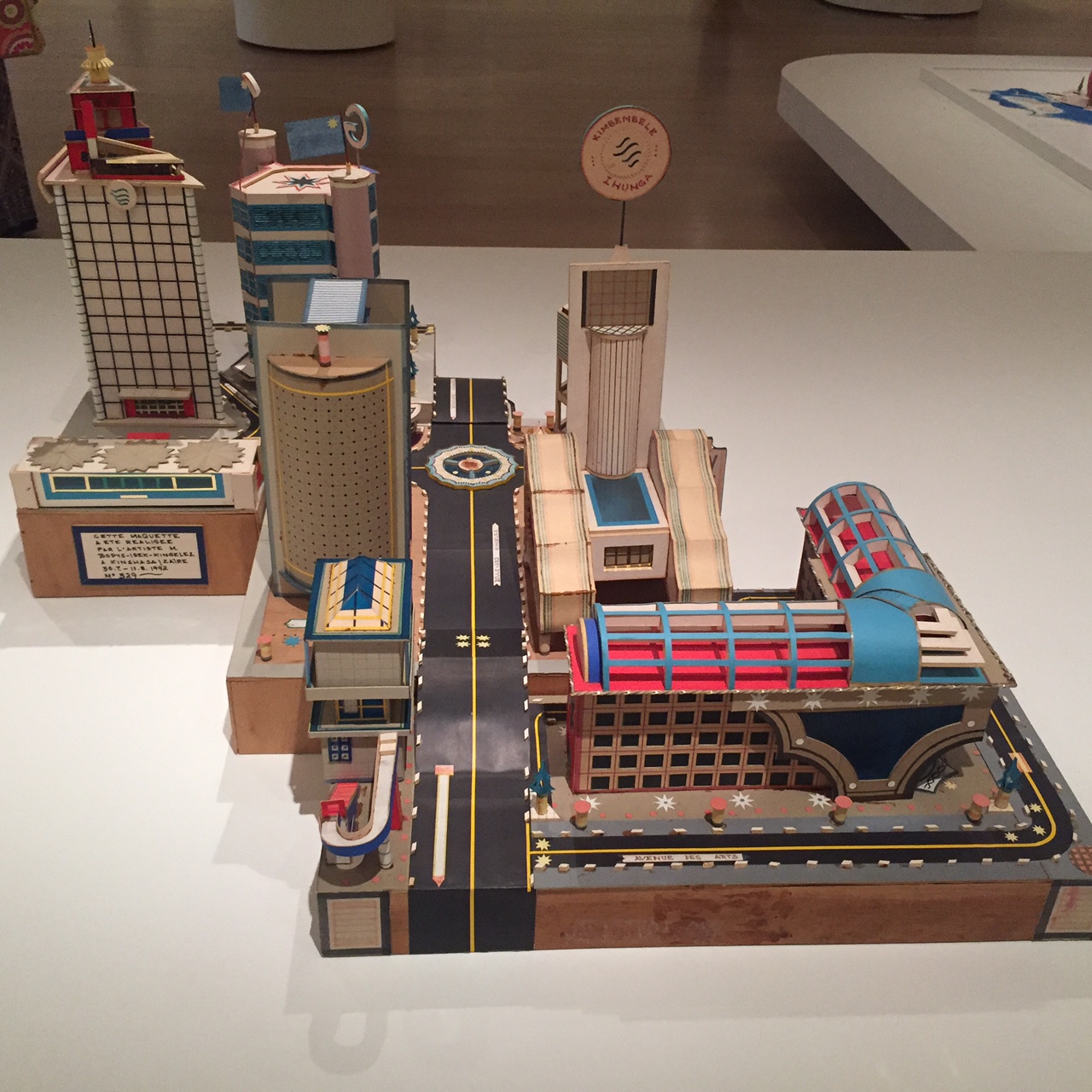

When you walk into MoMA’s third floor galleries and come upon the Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams show you think Lego, perhaps, or Stotsass. The colors are rich and varied, the fanciful structures charming. You might see the sparkle of gold and silver.

Then you get closer. You see urban purpose: the hospitals, the city streets, the libraries, the schools. You also see vision. You see that Kingelez calls his blue wraparound tiling, “butterflies”.

I’ve been in a lot of architectural model shops. All of them have a certain degree of ingenuity. Some are highly sophisticated, team efforts.

But Kingelez was a solo act, a shaman of sculpture, design and art. He cut and pasted his way to his version of an urban utopia. He wanted to help his country enter the free world armed with the tools it needed to survive.

Born in 1948 in an agricultural village in the then Belgian Congo, he came from a large family, received a missionary education, and moved to the capital Kinshasa in what became, after independence, Zaire. He studied to be a magistrate, a civil servant, became a school teacher, then a restorer. After six years of work at the local museum, he took his outsider art inside and became the artist he was destined to be.

In a fever of creativity, with razors, paper and glue, he began his lifelong quest to deliver an environment that defied violent regime change, illness, divisions among peoples.

In 1989 at Centre Pompidou, in an exhibition Magiciens de la Terre, curated to have 50 percent 'marginal' artists, he was finally introduced to the world. He received commissions in many countries. Still he always returned to his homeland.

Sarah Suzuki, the curator, says in spite of his vast artistic ambition, “the work is ordered, symmetrical, meticulously constructed.”

“He was forward facing and optimistic”, a creator of “extreme maquettes”.

Extreme how? In their civic-mindedness? In their quest for progress in the public sphere? Yes, today those realms may seem extreme as they slip through our President’s short, stubby fingers. “His work explores urgent questions around urban growth, economic inequity, how communities and societies function, and the rehabilitative power of architecture,” Suzuki writes, “with an incredible range of everyday materials and found objects—colored paper, commercial packaging, plastic, soda cans, and bottle caps.”

I have not had a chance to read the David Adjaye catalog essay, but I can see Adjaye being an excellent spokesperson for Kingelez. Any architect who sees this show will come away feeling somewhat chastened. It's so easy to be beaten down by the challenge of getting your vision built.

There’s a VR short film to “help people to understand it”says Suzuki—but really I don’t think you need VR to be responsive to Kingelez. Are we to have nothing left to our own imaginations with the advent of VR? It’s so literal-minded.

Carsten Holler did the install and it’s audacious. Almost all the maquettes are not in vitrines, but on lazy Susans or entirely exposed on low platforms. Suzuki has been brave about leaving most of the pieces within easy reach and the lenders too have been brave about letting such complex fragile work out of their sight. It befits the artist’s welcoming vision.

Jean Pigozzi has been collecting Kingelez (and many other African artists) for many years and is a major lender to the show. He says, “ He was fun, very bright and talkative. And a great dancer.” Pigozzi is proud that Kingelez is the first contemporary African artist to have a show at MoMA.

Attention all artists: People have been asking what artists can do in our current political climate to make a difference. Bodys Isek Kingelez, had the answer. He stayed true to his optimistic vision of a society where art commingled with education, religion and could make progress in spite of corruption. His glorious, colorful remix of paper, glue and a razor’s edge is a welcome, joyous reminder of the power of art.